Readers are also directed to the Licence holder performance | ARPANSA page to see the performance of individual licence holders.

This page provides information on the outcomes of source and facility inspections. Areas for improvement and learnings are shared here to inform licence holders of common issues, potential strategies to address their causes, and lessons to be learned. ARPANSA also recognises good practices where licence holders have ‘gone above and beyond’ the baseline requirements for safety and security. Good practices are shared here as learning opportunities for other licence holders.

Good practices

The following practices show how licence holders are using technology to enhance safety:

- Introduction of external video cameras capable of providing safe observation from outside the laboratory when examination of radiological materials takes place thereby limiting the risk of exposure.

- Development of an electronic source inspection checklist to assess the compliance of controlled apparatus against relevant codes and standards, internal requirements and other conditions of the licence.

- Use of computer-aided modelling of floor plans and the layout of indoor areas to identify areas of potential exposure and establishing safety boundaries when industrial radiography is performed.

- Radon remote sensing monitors allow real-time radiation protection to be available prior to entry to waste stores.

- Motorised laser alignment systems and software allow remote fine tuning to reduce accidental exposure risk.

- Use of ‘Take 5’ system (Stop, Think, Identify, Plan, Go Safely) for smart phones and tablets encourages staff to conduct a risk assessment prior to commencing a task.

Other examples of good practice:

- Use of a specifically designed source transfer port between laboratories to mitigate handling risks when moving unsealed sources.

- Emergency safety and security demonstrations based on real operational experiences are used to supplement regular emergency desktop & site exercises.

- Safety-related operational scenarios are included in operators’ training manual. Scenarios and steps to be taken appear on posters around the facility.

- Use of individual sign-on codes for multiple users accessing the same apparatus provides an auditable trail for use and assessment.

- Portable apparatus has a ‘power lock out’ attached to the power cord with a key lock preventing unauthorised use. The key is held by the person responsible for the device.

- Communicating the maintenance schedule of plant and equipment at weekly meetings ensures staff are aware of any maintenance issues with a potential to affect safety.

- Regular familiarisation visits of major facilities by emergency response personnel increases situational awareness.

- Maintaining a photographic record of sources in storage with clearly labelled packaging/containment assists audit and minimises time taken to locate.

Training

Training is important to provide people with the skills, knowledge and attitudes required to safely perform their job. This can be particularly important for new staff and for rarely performed tasks including emergency response.

Strategies to implement a systematic approach to training include:

- Perform a training needs analysis to identify the competencies and experience required to perform particular tasks or roles

- Implement software to track training and staff competencies, and capture training needs at an individual level

- Implement formal teaching and mentoring systems in the workplace to help promote teamwork and share lessons

- Implement or review succession planning and business continuity arrangements to ensure that critical skills are not held by only one or two people in an organisation

- Evaluate the effectiveness of existing training to ensure that training is relevant to the tasks being performed.

Managing changes

Changes are a normal part of operations, but some changes have significant implications for safety and need regulatory approval while others only require notification.

Significance is assessed based on the potential harm that may be caused by the change, including where the change may be inadequately planned or improperly carried out. When considering your request for approval, we assess the inherent risk and residual risk after any physical and administrative controls are in place. We have guidance to help you determine significance and understand the requirements of sections 63 and 64 of the Regulations.

Organisations need to have a wide range of measures to identify and control risks and hazards. However, even with high-level controls, some risks can easily be missed as they can depend on specific situations and changing processes. People should be actively identifying and assessing risks as part of their normal work and feel empowered to stop activities they consider unsafe.

Why changes are not reported

In many cases, the change control process does not include an explicit assessment of the safety significance of the change and fails to capture the regulatory requirements. To be effective it needs to consider safety impact, internal review and approval procedures, and external regulatory approvals or notifications. In some cases, the change control procedure may not be well established, may be unknown to relevant staff, difficult to apply, or only followed in an ad hoc fashion. In other cases, changes are not recognised when they occur.

Improving risk assessment

Strategies to promote and improve risk assessment and control across the organisation include:

- Use formal tools such as: Task/Job Hazard Analysis (THA/JSA), change management processes, regular risk reviews

- Use informal tools such as: Take 5, HAZOB, Pre-start checks, Toolbox meetings

- Regularly review operating experience and promote curiosity when things do not happen as expected, even when there is a good outcome

- Create, use and disseminate information such as risk registers and organisational learnings.

Australian New Zealand Standard AS NZS ISO 31000:2018 Risk management – Principles and guidelines provides useful information on managing risk in the workplace.

Improving configuration control

Configuration control is active management of the physical configuration and operation of sources or facilities (see Performance Objectives and Criteria) ensuring that safety margins are maintained. It is important to understand that configuration control includes the design and physical condition of what you have as well as how it is used and maintained. Good configuration control ensures you have an accurate picture of the state of your actual operation and that you identify the safety impact of any operational changes. For example, replacement of a device or component could change how tasks are done. Change is not always planned - for example, it can happen due to breakdowns, changes in staffing, or obsolescence/ageing. ARPANSA inspectors have found that licence holders don’t always document or evaluate changes. They don’t always apply for prior approval or report that changes have occurred in accordance with the Regulations. Configuration control is a common area for improvement and several licence holders have been found in breach of the Act for such failures.

Improving change control

Your management system should assist you to identify when changes occur, when they need to be made and how to assess both the nature and consequence of the change. Differences between activities and procedures are a common scenario where necessary changes may not have been identified.

A method for determining the safety significance of proposed changes (i.e. whether section 63/64 applies) should be explicit in a procedure or in your change process. The regulatory guide When to seek approval to make a change with significant implications for safety (section 63) describes how to categorise changes and can be integrated into your procedures. The level of consideration and detail will depend on the overall risk with higher risk facilities requiring greater defence in depth or safety controls. For less complex activities a page long checklist highlighting the key considerations may be appropriate.

Involving or including expert radiation staff in your multidisciplinary team to manage a change will help you identify and flag radiation safety issues. Investigating any barriers and challenges associated with adherence to change control procedures and how to make it easier will also lead to improved performance in this area.

Reporting

Reporting radiation measurements without context

The significance of radiation measurement data is often only understood by technicians or experts with experience, which means those who are unfamiliar with the context of measurement may not understand the significance.

Some examples of where radiation measurements have been reported without context:

- Staff perform the same cleaning actions for high readings as low readings, leading to extremity doses above statutory limits.

- Reviewers do not act on readings performed by other staff as they are expecting to see different units (μSv vs mSv).

- Instrument readings recorded were not compared with a standard or action level and therefore staff cannot tell whether the sample has passed or failed. Further details such as detector details/response and efficiency, method of collection, area sampled etc. are not available for the staff member, therefore a judgement cannot be made.

Why context is missing

Radiation equipment can give readings in many different formats, ranges, and radiation type (α/β/γ). Readings can be instrument readings such as counts per second (CPS), SI radiation quantities such as sieverts (Sv), becquerels (Bq), and derived units such as Bq/cm2 or mSv/hour. There are also non-SI units which can cause confusion, for example working levels, roentgen equivalent man (REM), dose/kerma area product (DAP/KAP).

In addition, readings can be instrument specific, be energy or radionuclide dependant. If a generic template is used, it might not have the correct context if it is made for a specific radionuclide or radiation type. For example, there could be different exemption or action levels for gross alpha/gamma or Co-60. People may feel it is ‘safer’ not to put context onto a form because they are worried it might not be correct if it is used in a different situation. However, without an indication of the range expected, unsafe situations can arise as described above.

Possible solutions

Providing an expected range and context can help the transfer of information/communication between staff. This can draw attention to results outside the expected range for all staff and help reviewers/experts make a judgement on the meaning of what is recorded. For example, when receiving a medical result such as a blood test the reading is printed next to the expected range (e.g. TSH 1.69 mIU/L [0.4-3.5]) which is then interpreted by the doctor to infer normal thyroid function. Similarly, in radiation, a reading with context helps to focus attention, but interpretation typically requires expert analysis.

Where possible a reading should be related to a limit, typical range, detection level or action level. Possible context for radiation measurements include:

- 20 cps [limit of detection ~ 3cps (~10 Bq/cm2)]

- 400,000 Bq [exemption limit 1,000 Bq]

- 0.5 Bq/g [exemption limit 1 Bq/g]

- 10 μSv/hr [typical working range 1-20 μSv/hr]

- 1 Bq/cm2 [limit for clearance 4 Bq/cm2]

- 3 Bq/m3 [DAC (I-131): 400 Bq/m3] (Derived Air Concentration limit)

- 2.1 mSv/year [Natural Background 1.5mSv, CT scan 5mSv, Occupational Limit 20 mSv]

Where instrument-specific units are used geometric efficacy should be provided for specific radionuclides or radiation types to ensure that the readings are interpretable at a later date.

Managing documentation

Processes or procedures not reviewed & updated

Regular review of processes, procedures and instructions is an important part of any safety system. The review and upkeep of documents demonstrates that risks continue to be adequately controlled and that work is undertaken as designed.

Workplaces are dynamic environments where personnel, equipment and work requirements change. Work practices tend to drift from how they were originally designed as people perceive easier, more efficient and better ways to complete tasks or adapt to new equipment and work demands. Where processes or conditions have changed without proper evaluation and documentation, risks may not be identified or properly controlled. There are many examples where this has unknowingly led to unsafe practices or accidents.

Strategies for improving and maintaining effective document control include:

- Implement a robust document management system/software which identifies the date when each document is due for review and who is responsible for the document. This may also help to reinforce personal ownership of documentation

- Implement workplace audit programs to verify that work is undertaken as specified in procedures and instructions

- Perform a ‘needs analysis’ to ensure all relevant stakeholders review procedures which affect them

- Raise the importance of regularly reviewing documentation, such as though the use of key performance indicators or attention at senior meetings

- Promote a workplace culture in which processes, procedures and instructions are followed accurately but, where ideas for improvement are welcomed and implemented with awareness and management of any related risks and opportunities.

Maintaining consistency between documents

Plans and arrangements for managing safety (P&As), typically including a radiation management plan, are submitted to ARPANSA during the initial licensing process. They must be maintained and updated at least every 3 years (section 61 of the Regulations). P&As are used by ARPANSA in assessments & inspection planning. On occasions it has been found that changes to other key documents such as standard operating procedures (SOPs) are not reflected in higher level documents (e.g. not listing or linking new equipment types or sources to the P&As).

The P&As should be useful and effective for the organisation and followed by those who are required to refer to them.

The same is true of the Safety Analysis Report (SAR); this is designed to be a living document but often is not updated as frequently as SOPs and other related documents, leading to inconsistencies over time.

Why SOPs are being updated while higher level documents are not

In general, SOPs are likely to be updated more frequently as they need to be used more often than higher level documents. Reasons why P&As or the SAR are not updated with SOPs can be human, technological and/or organisational. For example:

- A human factor observed is when the person responsible for updating or monitoring P&As/SAR changes, the responsibility is not reassigned or known during handover.

- A potential technological factor could be difficulties experienced with change and document control management systems, e.g. There is no indicator or reminder to update the P&As/SAR.

- An organisational factor could be how the organisation perceives and approaches the purpose of the document. When an organisation writes a document (P&As) for the regulator instead of preparing it as an operational document, this can create gaps between what is proposed, and what is done in the workplace and observed by inspectors.

To prevent higher level documents becoming out of sync with the SOPs, the review task should be part of routine operation – with sufficient resources for the staff involved in updating the information. This can include:

- Developing prompts for relevant staff so they can efficiently make changes to key parts of the plan as changes occur

- Ensuring changeover tasks are communicated and guidance available, especially for those who are new or covering a role

- Identifying all related documentation to ensure changes are consistent

- Organising sufficient time/resources for ensuring updates can be completed within workloads

- Looking at ways to streamline the process, including how obstacles can be overcome at an organisational level

- A change management system which is proactive in identifying necessary changes and making them in a timely manner

- Understanding how the documents reflect safety in a holistic manner (see Holistic Safety Guide and Sample Questions)

- Knowing when changes need to be reported to ARPANSA (see Additional Tips here)

While ownership of high-level documents is often with senior management, having operational staff involved helps keep them aware of changes and is a way to facilitate proactive safety management. Regular reviews with staff who need to enact the P&As/SAR is critical to ensuring that they reflect how work is conducted, the latest SOPs, and radiation safety challenges that need to be addressed in a continually changing industry landscape.

Deviating from procedures

There can be many reasons why procedures are not followed. Even the best people make mistakes.

Deviation from procedures may also be deliberate, although it is seldom of malicious intent. People may find that a procedure is poorly designed and cannot be followed completely. People are flexible and intelligent beings with a natural tendency to find and implement easier, more efficient ways of working. A danger of this type of deviation is that it may be undertaken without adequate awareness of the safety implications.

Careful consideration of the circumstances which led to people not following procedures could uncover some important underlying issues. Strategies for addressing deviations from procedures include:

- Review procedures taking into account human factors. Where the workplace, equipment and procedures are designed with the user in mind, taking account of human capabilities and limitations, people can work effectively with technology. This can reduce the likelihood that workers deviate from the defined procedure when they think there is a better or more efficient way to perform the job.

- Audit work practices to determine if they are being carried out to procedure. If not, understand the reason and implement change control measures or training as appropriate.

- Review change management and document control measures to ensure that where processes are changed, procedures are also updated.

- Review workplace training and supervision arrangements, with a focus on ensuring that all staff are sufficiently familiar with a task or procedure. See staff training section below.

- Promote safety culture across all layers of the organisation to ensure that unhealthy workplace cultures do not affect individual’s performance. For example, production pressure can cause the perception that production is more important than following procedures or safety requirements.

Equipment or facility issues

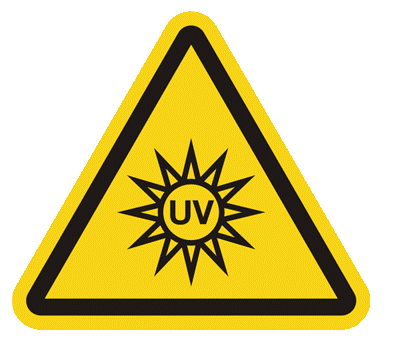

Incorrect UV signage

UV equipment without the correct signage/warning labels accounted for 30% of all incorrect signage found in ARPANSA inspections over the last 3 years. This affected a range of UV sources used in biological safety cabinets (laminar flow or biohazard) and transilluminators.

Signage requirements are set out in RPS 12 Radiation Protection Standard for Occupational Exposure to Ultraviolet Radiation (2006) and Australian Standards such as Australian Standards AS 2243.5 NIR laboratory standard (2024). Instead of Australian Standard compliant signage, often signs from Europe or the USA are used. There is a risk of confusion and lack of hazard awareness if signs are inconsistently used across the industry.

|

|

|

|

|

| Correct - AS 1319 Safety signs for the occupational environment (1994) | Correct – AS 2243.5 Safety in laboratories, Part 5: Non-ionizing radiations - Electromagnetic, sound and ultrasound (2024) | Incorrect - ISO 7010 symbol for optical radiation (not currently adopted in Australia) | Incorrect – not to be used - only used for lasers | Incorrect – not to be used - only used for ionising radiation |

Causes of incorrect signage

When UV equipment is purchased from overseas, online or through a supplier it often comes with overseas warning labels attached. As these types of sources are not regulated by most states and territory radiation regulators, suppliers and staff may not be aware of the correct labelling.

Improve signage

To prevent the use of incorrect signage, you should perform your own checks of equipment against applicable standards periodically and when changes occur (such as when commissioning new equipment). The frequency of checks should be graded based on risk, inventory, and the frequency of changes. It is typically a requirement of most ARPANSA licences that these checks are carried out at least every 3 years. You may purchase UV signage or print and stick UV signage for your needs, ensuring the image features, ratios and colour are accurately reproduced as they appear in the relevant standard.

To assist in carrying out these self-assessments ARPANSA has, in conjunction with licence holders, developed a checklist for UV apparatus that is available online through the iAuditor website. This app allows you to perform the checks and submit results to your radiation safety officer or to ARPANSA.

You should consider how checks are integrated with your current safety and compliance monitoring processes. Performing self-checks demonstrates a proactive approach to compliance and is supported and encouraged by ARPANSA